For most, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) happens when the days are short during the winter. 3 percent of Americans have

winter-onset SAD, and nearly 7 percent of individuals with depression have worse symptoms during winter.

SAD is more than just the “winter blues". It is a seasonal form of mild to moderate depression tied to the increasing levels

of darkness and the sun’s lower position in the sky. During the winter season, individuals with SAD experience lower energy levels and poor mood.

SAD symptoms usually start and end at the same time for affected individuals each year (with the changing of the seasons in

late fall or early spring). In what’s known as reverse SAD or summer-onset SAD, one out of ten SAD patients experience it in the summer.

Symptoms of seasonal affective disorder

People with SAD experience the following symptoms of depression for a period lasting roughly 5 months (through the length of

the season):

-

Low energy levels

-

Difficulty concentrating

-

Depression, including feelings of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts

-

Loss of interest in formerly enjoyable activities

-

Appetite and weight changes

-

Trouble sleeping, feelings of sluggishness and/or agitation

Some of these symptoms present oppositely depending on whether the individual has winter-onset or summer-onset SAD (meaning

the disorder affects them during the winter or summer, respectively):

To be diagnosed with SAD, a person must experience these symptoms at a significantly higher rate or intensity during the

winter or summer season.

Changing seasons may also affect individuals with bipolar disorder, inducing depression during the fall and winter months

and mania during the spring and summer. If an individual has depression as well as SAD, they typically experience worse symptoms during the winter.

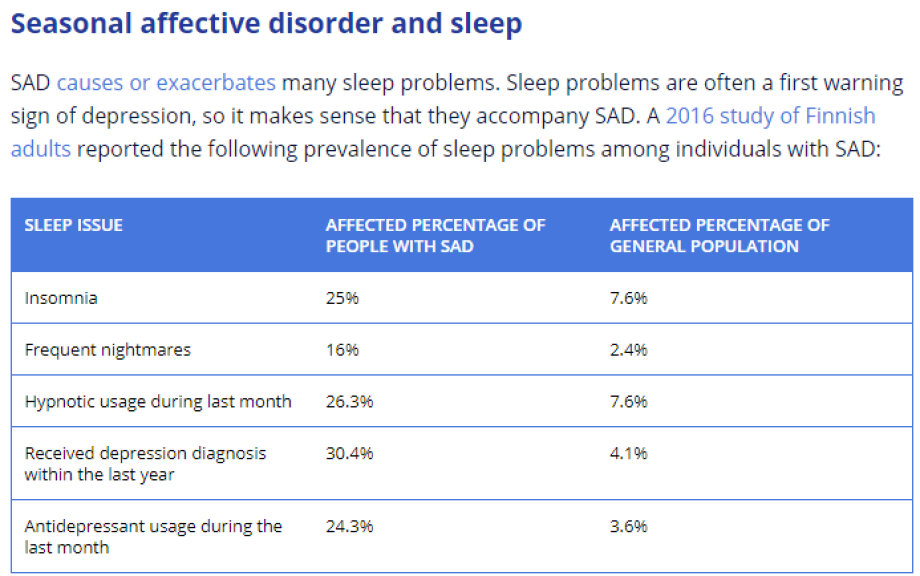

People with SAD are more likely to be night owls, and to sleep either for too long or for too short (fewer than 6 hours or more than 9).

The biggest sleep issues for people with SAD are hypersomnia, insomnia, or both. Although, hypersomnia is much more

common, affecting as many as 80 percent of people with SAD. There are good evolutionary explanations for this.

The paucity of food in Winter should drive ancient humans to sleep more and consume fewer calories.

Even when they do sleep, that sleep may not be as restorative as it could be. Brain studies show that when SAD strikes, the efficiency of sleep (percentage of time in bed spent asleep) decreases, and the amount of time spent in

deep sleep decreases while the time in REM actually increases.

Speaking of sleep efficiency, people with SAD spend a lot of time in their beds, causing many to mistakenly that

they’re getting a lot more sleep than they actually are. This can prevent them from getting properly diagnosed, and cause undue anxiety or concern about why they

feel so tired during the day (when they think they’re getting enough sleep).

Can weather affect sleep for people with SAD?

Daily circadian

rhythms are closely tied to the sleep-wake cycle, but SAD shows an example of another natural cycle that affects

sleep. You might call these circannual rhythms. In some animals, circannual signals such as temperature and rain patterns can trigger physiological changes. The light levels and position

of the Sun in the sky are among those proximal cues.

In other words, other environmental factors besides light influence sleep. Cooler temperature facilitates sleep, and the outside wintry air may contribute to the hypersomnia associated with winter depression. On the

flipside, the heat and humidity associated with summer makes it tougher to cool down and be comfortable enough for sleep – contributing to summer insomnia.

Treatment for SAD-related sleep problems

For many individuals with SAD, symptoms naturally go away with the changing of the seasons. However, until that point, there

are several things they can do to feel and rest better.

Therapies

Because the many people with SAD experience insomnia, or share the same kind of

thoughts that keep insomniacs up at night, therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy for

insomnia (CBT-I) may be helpful. In CBT-I, the therapist works with the patient to help them

recognize thought patterns and behaviors that prevent them from falling asleep, so they can replace those with better thoughts and new habits that facilitate sleep.

Light

therapy – exposure to a strong artificial light – works extremely

well for this type of depression. Patients sit in front of a light box for 30 to 60 minutes in the morning (those

falling asleep too early should use it in the evening instead). The lightbox uses 10,000-lux bright white fluorescent bulbs to simulate the sunlight, but in a safe way without the UV rays. Some of

these (known as “dawn simulators”) are meant to simulate dawn and turn on gradually in the morning.

Source:Tuck.com